CAR industries can be successful. Just ask the Germans, Japanese, Americans, South Koreans and, more recently, the British.

Figures released from the UK Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders show the UK is on track to produce about 1.8 million cars this year, almost double what it produced in 2009 following the GFC. And not bad for a market that registers about 2.7 million cars annually.

It’s a return to form for an industry that has been through ups and (many) downs.

And it’s proof that first-world countries with relatively high labour costs can have a viable car industry.

Not that it’s as simple as that.

The UK government – with the support of the public – has poured plenty into supporting the industry over the years, and being close to mainland Europe provides an easy (and open) market for cars, including high-margin ones the Poms do so well.

Perhaps the strength of the brands doesn’t hurt, either. England has created some of the most iconic brands in automotive history: Rolls-Royce, Bentley, Range Rover, Mini and Aston Martin. Even though each is owned by others these days, the thought of losing some of the biggest brands in the world could not sit well with some.

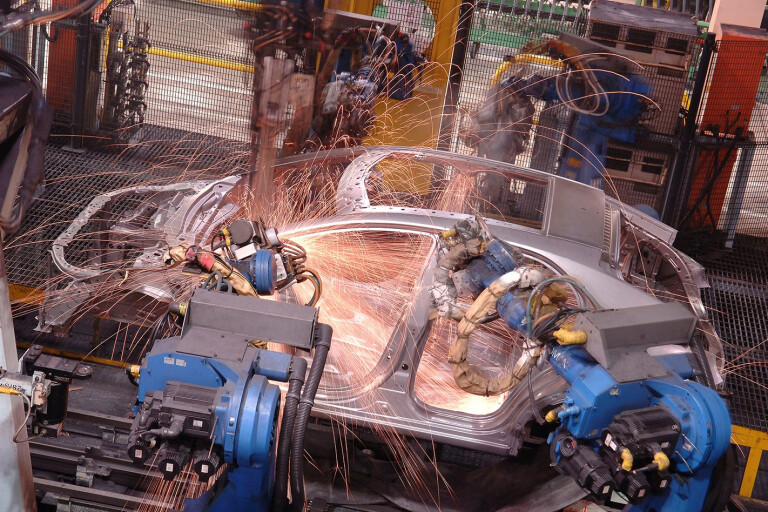

But the cars giving the UK its manufacturing might these days are Nissan, Toyota, Opel (through Vauxhall), Honda and BMW (through Mini). A manufacturing environment established over decades has proved appealing enough for some of the world’s biggest manufacturers to invest in, weathering the storms when things aren’t so good.

So, ironically, the saviour of the British car industry has been car makers from other parts of the world, in turn contributing to a thriving components industry and an appetite for vehicle manufacturing that has no doubt helped British brands.

The most popular brand in the UK, Ford, imports all its vehicles, although it does maintain a significant UK manufacturing presence through engines and transmissions.

And, again, it’s international money that has helped the British industry survive. Even Jaguar and Land Rover live on money and direction from Indian giant Tata, a company that has, cleverly, created an environment that allows the English to produce better cars for the world.

It’s tempting, then, to make parallels with the Australian manufacturing industry, which shuts down on October 20 this year when Holden closes its Elizabeth plant.

But that would be ignoring the enormous scale and diversity in the UK industry. In its depths it was producing 1 million cars, and they still covered a broad range, from low volume sports and luxury cars to mainstream models across multiple brands.

As has been well chronicled, Australia was hooked on large cars – something the public was demanding – so when the tides turned it was difficult to react quickly, or with the numbers required to make things work.

Boats can easily transport cars elsewhere, but Australia is further from its prime export markets than the UK is from its.

And Australia’s closest markets were even closer to a steady stream of vehicles from factories with lower costs than ours.

Little wonder that in 2014 the Productivity Commission recommended Australians stop supporting the automotive industry, as difficult as it was for many to swallow.

Falcon ute bows out two months ahead of Ford manufacturing shut-down

Of course, the Australian industry is not entirely a victim of circumstance.

In researching a book on Holden, former Holden boss Peter Hanenberger told me of an early-2000s agreement between the car makers (then Holden, Ford, Toyota and Mitsubishi) to receive $2.5 billion in assistance with the view to being off support entirely by 2015.

“[John] Howard had a clear understanding of what the auto industry should be in Australia,” said Hanenberger back in 2015. “It was under the Howard government with [Ian] MacFarlane that we negotiated a deal … that we committed to have no more support by the Australian government.”

Since then a major shift in the market occurred whereby large car sales dived and SUVs boomed, in turn fragmenting the market and reducing that scale that is crucial to a manufacturing industry.

Tariffs were also being wound back on imported cars, although that was something the industry was aware of and working to combat.

So, while that early-2000s plan may well have been achievable, history will show it wasn’t.

COMMENTS