First published in the November 1989 issue of Wheels magazine, Australia's best car mag since 1953.

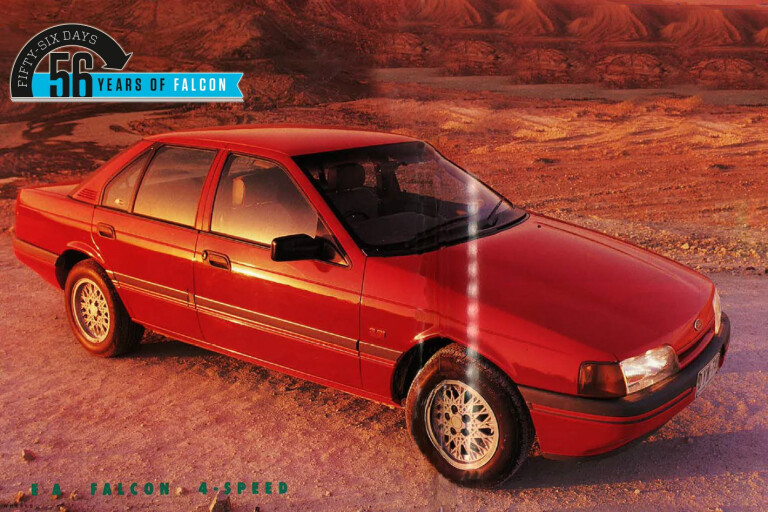

The big Ford at last gets the four-speed auto it needed. Other subtle changes help make the 1990 Falcon a much improved car.

IT'S NOT OFTEN that a car is judged on the strength of a new automatic gearbox, but Ford is pinning a lot of hope on what has been loosely termed the EA Falcon Series II, the chief merit of which is a new automatic gearbox. This is the locally designed and locally built unit that should have been in the EA Ford Falcon from Day One.

In fact, the EA engines were specifically designed to mate with this box, which goes some of the way towards explaining why the Fords have so far never really felt or sounded happy with the three-speed auto. Indeed, the transformation is surprising, and tends to reveal things we may never have expected of the Ford overhead cam engines.

Now that extra ratios are available, there's no longer any real problem with the engine's torque range. There are also gains in bottom-end performance and fuel economy, and in general driveability.

The 85LE four-speed auto, four years in the making after the design was set in late 1985, was developed by BTR – the current incarnation of Borg Warner in Australia- and represents $100 million in development costs. it is an electronically controlled unit that differs mainly from other electronic boxes in the fail-safe techniques used.

Testing procedures have benefited from the delayed release. In May this year Ford built 200 cars off production tools and these had been in service at the time of writing for up to three months. Earlier, in October 1988, 30 cars were put into service in various guises and some of these are presently nearing 100,000 km without, according to the engineers, suffering anything that could be described as a problem. The bench testing is also harder than it was for the three-speed.

Testing procedures have benefited from the delayed release. In May this year Ford built 200 cars off production tools and these had been in service at the time of writing for up to three months. Earlier, in October 1988, 30 cars were put into service in various guises and some of these are presently nearing 100,000 km without, according to the engineers, suffering anything that could be described as a problem. The bench testing is also harder than it was for the three-speed.

Durability runs on the dynamometer now extend to 360 hours, compared with the previous 150 hours, while the shift cycles have gone from 7000 to 10,000.

The 85LE is, as Ford takes pains pointing out, a new-age transmission that offers development potential ensuring its survival to the end of the next decade. The point being made here is that Holden's hydraulic THM700 transmission is nearing the end of its service life.

The four-speeder is slated for export markets, but the major user for the time being is Ford Australia, which will be taking 70,000 units a year - around 50,000 less than the capacity of BTR s factory in Albury, NSW.

The auto's operation, like other new-age electronic transmissions, is a combination of electronics, hydraulics, and straight mechanical action. Predominant among the things the designers are particularly happy about - and the subject of international patents - is the twin line pressure system, each of which is operated by its own solenoid. Put in simple terms, this means each line is dedicated to more specific tasks than your average auto. One looks after general transmission operation while the other tends exclusively to upshifts and downshifts. The fail-safe aspect comes via a watchdog component in the main system which notes the time taken for the change to take place, and steps in to complete the job if it's taking too long, signalling an incipient malfunction with a more harsh-feeling shift.

Internally the 85LE holds few other surprises. Because of the extra ratio it's heavier by around 20 kg than the three-speed, although there have no doubt been some weight gains because of the electronics. It also runs cool. Unlike the Holden auto, which will actually cause the air-con to shut down if it starts getting hot, II has no need for any special overheat protection, although an oil cooler is included when the tow pack is specified.

Internally the 85LE holds few other surprises. Because of the extra ratio it's heavier by around 20 kg than the three-speed, although there have no doubt been some weight gains because of the electronics. It also runs cool. Unlike the Holden auto, which will actually cause the air-con to shut down if it starts getting hot, II has no need for any special overheat protection, although an oil cooler is included when the tow pack is specified.

Ratios of the 85LE's lower three gears are identical to the old box, and fourth is an 0.69:1 overdrive. To spread things out better, Ford has gone for lower final drive ratios, so there's more bite down low while the overdrive looks after highway cruising.

Multi-point engines get a 3.23:1 differential to maximise performance, while throttle-body injection units use 3.08:1. Whatever the ratio, top gear engine speeds are down substantially multi-point autos give 100 km/h for every 1897 rpm, while the more frugal throttle-body requires only 1815 rpm for the same road speed. The old auto had the engine turning at 2450 rpm for 100 km/h. Little wonder then that Ford's claimed economy advantages favour the highway cruise.

Most models across the range, with the exception of the multi-point GL wagon and the Fairfane, which boast improved factory test figures, are quoted as identical on the urban cycle, but all benefit significantly on the open road by anything up to 1.4 litres/100 km.

The performance aspect is interesting. Ford's new auto still doesn't allow the multi-point to match the lighter Holden V6 off the line, although Ford engineers tell us their overtaking brackets are superior. Count on less than 10 seconds to 100 km/h and 400 metres in under 17 seconds with an automatic multi-point.

The big story however is the improvement to general driveability imbued not only by the four speeds, but also by the improvements in shift quality, and the vastly improved shift patterns. The 85LE box, like any respectable electronic auto, offers the choice of power or economy modes, and provides a lock-up on third and fourth ratios which is programmed similarly, in the selection strategy, to your actual gearshifts. The difference with other lock-up autos is that third gear lock-up only happens here when the selector is held in that ratio.

The big story however is the improvement to general driveability imbued not only by the four speeds, but also by the improvements in shift quality, and the vastly improved shift patterns. The 85LE box, like any respectable electronic auto, offers the choice of power or economy modes, and provides a lock-up on third and fourth ratios which is programmed similarly, in the selection strategy, to your actual gearshifts. The difference with other lock-up autos is that third gear lock-up only happens here when the selector is held in that ratio.

There can be no argument that the 85LE is straight away a sweeter transmission. Shifts from first to second and second to third are smoother- no doubt a legacy of the separate line-pressure systems - while third to fourth is close to undetectable. Ford is still working on refinement of the earlier shifts, but is happy with the competitiveness of the box at this stage.

The lock-up is arranged so that it will drop out on over-run - which helps minimise jerking and other misbehaviour when a trailer is being towed - and cuts in and out much the same as a proper gear.

The downshift strategy works through the four ratios, plus the lock-up top gear, with an eye on maximum advisable downshift speeds. It is generally unobtrusive, although Holden's THM700 is acknowledged as better in this area. The advantage with the Ford is that maximum downshift speeds are controlled on all gears, rather than just first, as is the case with the Commodore.

The selection pattern allows unrestricted movement without detent everywhere except first and reverse/park slots, and the economy/power selector switch, on floor-shift models, is on the console to the right of the T-bar. It's on the instrument panel of column-shift models.

Unlike some dual-mode autos, Ford uses the full range of four ratios when the power switch is on.

Unlike some dual-mode autos, Ford uses the full range of four ratios when the power switch is on.

Although there was never any doubt the Ford would 'be happier with a four-speed auto, it's liXely that few would have expected it to transform the EA to the extent it has. The engine feels sweeter, less obtrusive at speed. And it works its way through the shift range more comfortably than it did with the three-speed.

On dirt roads the Ford Falcon still feels nervous, although the car's overall handling has been improved by a host of suspension changes. A minimal slurring of the shifts takes away practically all of the harshness without dramatically affecting the continuous supply of power. Part-throttle downshifts come quickly without the histrionics some four-speed autos are prone to, and anticipate the driver pretty well. A floored accelerator will see the auto seeking out the lowest practical kickdown gear, but once again it won't get too radical with the carefully mapped downshift strategy, even in the more responsive power mode. Flat-out upshifts occur at similar, though not exactly the same, rpm in both modes.

Essentially, the tuning of the transmission - relatively easily achieved via the electronics, to the point that a complete change in characteristics can be effected in something like half an hour - has been executed in three different modes which suit the characteristics of the models concerned; throttle-body injected sedans are aligned towards a more economical style of operation, while Fairlane/LTD and Ghia models lean towards the performance side. In the middle are the multipoint GL and Fairmont sedans.

The NVH improvement comes from more than just the fact that there are extra gears to play with, and that they're selected more gently. Dampers attached inside and outside the driveshaft, a stiffer fixture of the engine to the transmission, a tuned mass damper, and a certain degree of compliance engineered into the system via a 'torsional isolator', all work together to smooth out the big Ford.

A bold further move in the cause of improved NVH in Fairlane and LTD models (and multi-point wagons) is the adoption of an aluminium driveshaft. This approach was chosen in favour of a more expensive, heavier and more complex two-piece driveshaft because it was considered better suited to lock-up transmissions, particularly during take-off and gearshifts. The 82 mm aluminium shaft from Dana in the US weighs between two and three kilograms less than a steel shaft and incorporates a tuned damper placed to minimise bending.

The overall effect of all this NVH work is that everything feels more refined and quieter on the road - which is saying something about the Ford which has not impressed so far on either count. Yes, this is a good automatic transmission. The arrival of the four-speed auto has also allowed Ford to introduce a number of cosmetic changes which are barely detectable inside or out, but are calculated to subtly upgrade the car.

The overall effect of all this NVH work is that everything feels more refined and quieter on the road - which is saying something about the Ford which has not impressed so far on either count. Yes, this is a good automatic transmission. The arrival of the four-speed auto has also allowed Ford to introduce a number of cosmetic changes which are barely detectable inside or out, but are calculated to subtly upgrade the car.

From outside. there's little more than a body-colour B pillar, a couple of new paint hues, plus a rear window stoplight to give the game away. Inside it's pretty much the same story. A few welcome touches such as the use of a spot of fabric on base-model doors, a centre console containing air ducts to the back, map pockets behind the front buckets, rear door ashtrays and new trim materials about cover it.

What's important is the stuff you can't see. Ford has been working away refining the EA since Job One, and although the Series II doesn't specify any mechanical changes other than the new auto, there's a lot that's different about the latest Fords.

Most significant is the progressive work that's been done on suspension. The underpinnings on today's Falcons, from GL through to Fairmont Ghia, now differ only in ride height from the S model.

Shock absorbers have gone from 25 mm to 30 mm across the board, springs went from 40 to 45 Nm in October last year, and front stabiliser bars, now mounted more effectively, have been upped to 26 mm from 23.5 mm, an increase even for the S which originally used 25 mm bars.

At the rear there have been fewer changes. Nothing has been done to springs or dampers, but closer attention is being paid to ride height, especially in self-levelling models which have tended to kick their tails up beyond the specifications, causing warranted discontent.

Criticism of driveline snatch in five-speed manual cars has been reacted to as well. Ford's team has worked on reducing driveline backlash by resetting the pinion nose wind-up in the rear axle, and firming the four lower-arm bushes.

Anyone who remembers how the original EA Falcons felt on the road will notice a big difference in the current model. Although some of the unsettling early model vagueness is still there, the car feels more secure, more accurate on the road - which is the positive side of a firmer, slightly less absorbent ride. The Watts linkage assists straight-line tracking ability on broken bitumen, but unsealed roads still leave the Falcon's rear end feeling a little unhappy.

Our new generation S test car showed a tangible improvement over earlier versions, even though the changes at this specification level are less extensive than anything else in the range. Basic understeer is still there, but the turn-in feels better and the car appears less affected by weight transfer in tight, alternating right and left corners. Considering the fundamental simplicity of the Ford's suspension it behaves well enough for a 1600 kg vehicle, although the S still doesn't go far enough for some of the engineers and we should see a less compromised version sometime early in 1990.

The EA Falcon, Series II, is the car Ford should have given us in early 1988. it's good enough to repair the corporate reputation damaged at the hands of a new design/development philosophy which people needed more time to adjust to, but it's not going to do that overnight.

For it is, after all, hardly a new model and doesn't have flash needed to drag the curious into showrooms. What it is, is an evolutionary, much improved Falcon that reinforces the old philosophy that you never, never go out and buy an all-new car as soon as it's released. You wait until the manufacturer gets to know his product, and learns to build it properly.

And, considering Ford sells only 15 per cent or so of its Falcons as manuals, there can be no harm in having what is arguably the best auto in the class.

COMMENTS