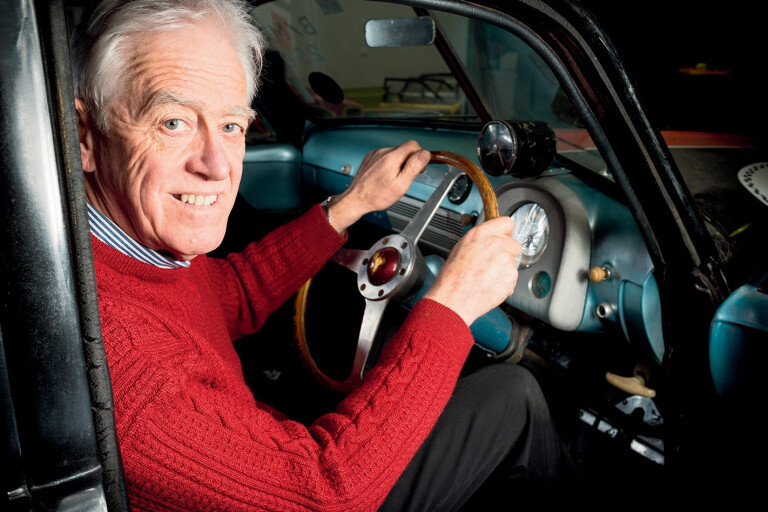

Motor racing’s go-to man for an engineering advantage.

IN 2014, Ron Harrop received a call from CAMS. The caller explained that he’d won the Phil Irving Award, recognising achievements in motor sport engineering. “I thought it was a joke at first,” Harrop recalls.

The only joke is that it took so long to acknowledge an engineer who was inspired by Irving himself, and whose intuition and passion took Harrop Engineering from a small family business to a 60-strong team supplying precision components to Formula 1.

Harrop was no less handy at the wheel, whether in his own V8 Sports Sedan or racing (and engineering) HDT Torana A9Xs.

In 1955 Ron’s father Len established Harrop Engineering in Brunswick, doing general engineering and fabrication. Ron qualified as a boilermaker and joined the business in the mid-1960s. “I was making low-loaders, truck trays, food mixers and all sorts of things.”

Leading racers Norm Beechey and Bob Jane had their workshops nearby and found that Ron had the intuition, skill and passion to make parts on race-tight deadlines.

A friend suggested he try drag racing and by 1972, with a custom, 12-counterweight crank made by Ron, his famed six-cylinder ‘Harrop’s Howler’ FJ had turned an 11.8sec quarter.

Similar story when Harrop went circuit racing, initially in a six-pot EH; later converted to a Sports Sedan using a Repco-Holden V8 borrowed from Jane.

Harrop caught the attention of HDT boss Harry Firth. “I started doing work for Harry and next thing he offered me a drive at Bathurst.” Harrop shared an A9X with Charlie O’Brien, finishing fifth, and did endurance races semi-regularly until 1986.

Throughout, Harrop was an unstinting innovator, putting his mind to improving every aspect of a car’s performance – whether brakes, clutches, gearboxes, suspensions or engines.

“I love a challenge. In my mind the easiest thing is the cure – it’s identifying the problem that’s sometimes the hardest part.”

In 1993 HRT enlisted him to shake up its engineering, a “full-time part-time” role he did for six years. “HRT suited me down to the ground because I had the opportunity to release things I had in my head.”

The motor sport industry by now knew that Harrop could turn his hand to anything.

“I was doing quite a lot of work for McLaren, especially when they came to Melbourne. Even from the UK, they’d email their drawings – they couldn’t believe they could generally get things made quicker than they could in their own workshop. During the race weekend we’d helicopter things to Albert Park from the helipad at the end of our street.”

Harrop remembers working such long hours he’d start hallucinating. “I have never done it for the money. I like to get paid, but there isn’t a waking moment where you’re not thinking about a problem you’ve got to surmount, or the next job you’ve got to do.”

Ron sold Harrop Engineering in 2008 and finally left it in 2013. The Phil Irving Award meant a lot because Irving helped shape who he is. “I was working with Norm Beechey and we had a problem with torsional vibrations in the crankshaft. And Norm said, ‘Well, ring Phil Irving’. And I thought, ‘You can’t just ring Phil Irving’. Norm said, ‘Nah, you’ll be okay.’

“Today, people can ring me up and ask a question if they think I can help, and that’s probably because of that.”

Harrop still delights in doing bespoke engineering work. He’s currently relocating to rural Kilmore from suburban Templestowe. “No room here for a shed.” ’Nuff said.

COMMENTS