.jpg )

Kiwi motorsport legend Bruce McLaren was killed 45 years ago, but, as Michael Stahl and a current 650S find, the memory of him in the Shaky Isles is still very much alive.

IT’S just on six years since McLaren announced its plan to launch a family of supercars designed, engineered and tested in close conjunction with the Formula One team. As promised, three distinct series have blossomed from essentially the same MonoCell carbonfibre chassis and twin-turbocharged 3.8-litre V8.

The MP4/12C laid the groundwork in 2011. In late-2013 McLaren launched the range-topping P1, a 673kW hyper-hybrid. In March last year came the mid-range Super Series 650S, a 12C turned up to 11. The new entry-level Sports Series, initially comprising 540C and 570S, was unveiled in March this year – at the same time as a Super Series 675LT, spiritual successor to the F1 GTR ‘longtail’ racer of 1997.

There’s little faulting the technology, performance, comfort or obsessive attention to detail in the products of McLaren Automotive – all, apparently, a reflection of the notoriously nit-picky Ron Dennis, who has steered the company since 1980.

If you hear any criticism of McLaren cars, it’s usually that they lack soul. We’re taking a shiny new 478kW McLaren 650S Spider to see if we can find it. Not within the NASA-like environment of the McLaren Technical Centre in Woking, Surrey, but in a quiet suburban workshop in Remuera, Auckland, New Zealand.

If you hear any criticism of McLaren cars, it’s usually that they lack soul. We’re taking a shiny new 478kW McLaren 650S Spider to see if we can find it. Not within the NASA-like environment of the McLaren Technical Centre in Woking, Surrey, but in a quiet suburban workshop in Remuera, Auckland, New Zealand.

Seventy-nine years ago, second-generation motorcycle racer Les ‘Pop’ McLaren bought the lease to this garage and moved his wife Ruth and daughter Pat into the flat above. A year later they welcomed a son, Bruce Leslie McLaren.

Return to the heartland

OUR trip begins in nearby Grey Lynn, where McLaren’s Auckland showroom opened in 2013. Appropriately, it’s owned by Sir Colin Giltrap, who knew Bruce McLaren in the early years and who has been a strong and consistent supporter of Kiwi motor racing talent.

Plenty of people think of McLaren as a British brand, but there are no such misconceptions among Kiwis. The 16 McLarens sold in 2014 make New Zealand the only market in the world where the brand has outsold Ferrari (15 cars; admittedly down from 20 the previous year).

Plenty of people think of McLaren as a British brand, but there are no such misconceptions among Kiwis. The 16 McLarens sold in 2014 make New Zealand the only market in the world where the brand has outsold Ferrari (15 cars; admittedly down from 20 the previous year).

“I thought we might get the odd boffin with some money tucked away,” explains sales boss Luke Neuberger, who came to McLaren Auckland after 10 years selling Ferraris. “But I’ve sold at least four or five cars to guys who say, ‘I grew up watching Bruce McLaren race’. The loyalty is very, very strong.”

A much younger generation has little knowledge of McLaren and Denny Hulme, local boys who won grands prix, won Le Mans, raced at Indianapolis, dominated Can-Am racing and created, with just a few dozen disciplined men – many of them fellow Kiwis – a powerhouse racing car company on the opposite side of the world.

That doesn’t save Neuberger’s cleaning staff any money on Windex after each weekend. “It’s mainly young kids,” he says of the marks on his showroom windows. “They know everything about McLaren cars – the P1, the 650S, the 12C – because of [gaming console] Xbox.”

That doesn’t save Neuberger’s cleaning staff any money on Windex after each weekend. “It’s mainly young kids,” he says of the marks on his showroom windows. “They know everything about McLaren cars – the P1, the 650S, the 12C – because of [gaming console] Xbox.”

Our white McLaren 650S Spider, a $505,750 proposition in Australia, certainly has the goods on the earlier, somewhat anonymous 12C. The slashing headlamp treatment echoes McLaren’s current ‘speed marque’ (aka ‘sea slug’) logo, though I was happy to see the logo replaced on the 650S’s nose by the McLaren name.

Squint and you might see a lineage to the ground-breaking McLaren F1 of 1994. Squint harder, perhaps through the coastal mists that often veil this narrow neck of land, and you might even see the M6 GT, the Can-Am-based coupe of 1969 that was intended to take McLaren into Group 4 GT racing and then onto the road.

McLaren likes to boast that the 650S, at a claimed dry weight of 1330kg (for both coupe and spider), is within reach of Ferrari’s stripped-out 458 Speciale coupe/spyder (1290/1340kg), and as quick or quicker on a racetrack. Yet the McLaren retains a full complement of comfort kit, hydraulic suspension lifting for low-speed clearance, and hugely intelligent active aerodynamics that, for example, won’t retract the airbrake wing if the car is in a high-speed bend, or lofting a crest.

McLaren likes to boast that the 650S, at a claimed dry weight of 1330kg (for both coupe and spider), is within reach of Ferrari’s stripped-out 458 Speciale coupe/spyder (1290/1340kg), and as quick or quicker on a racetrack. Yet the McLaren retains a full complement of comfort kit, hydraulic suspension lifting for low-speed clearance, and hugely intelligent active aerodynamics that, for example, won’t retract the airbrake wing if the car is in a high-speed bend, or lofting a crest.

The scissor-lift doors make entry easy in parking spaces, the seats are truly comfortable, and the interior quality impeccable. On the centre console, a pair of rotary controls marked H (for handling) and P (powertrain) each offers Normal, Sport and Track settings. The cockpit’s rear window may be lowered, as part of the roof’s Z-fold operation – or just to better hear the engine.

Leaving the City of Sails via the Auckland Harbour Bridge, the mighty Mac’s snarling 478kW and eerily seamless seven-speed paddle-shift transmission are for once less amazing than its comfort and ease of use.

Leaving the City of Sails via the Auckland Harbour Bridge, the mighty Mac’s snarling 478kW and eerily seamless seven-speed paddle-shift transmission are for once less amazing than its comfort and ease of use.

The 650S has stepped up considerably from the 12C in suspension stiffness, but McLaren’s linked active dampers, which dispense with the need for anti-roll bars, deliver intimate feel and likeable ride.

History in the making

On Auckland’s north shore is the seaside suburb of Takapuna. Here, Bruce McLaren spent almost three years of his early life – from age 10 to 12 (1948-50) – at the Wilson Home, a forward-thinking treatment centre for children with serious disabilities.

Bruce had Perthes Disease, in which the ball in the hip joint can grow mis-shapen. Such diseases – most visibly, polio – were treated by immobilising and straightening the limbs. McLaren, his legs in traction, was strapped to a bicycle-wheeled wicker gurney. Just 10 years later, as the youngest driver to have won a Formula One grand prix (the US GP in 1959), McLaren paid a return visit to the Wilson Home with his Cooper GP car.

Bruce had Perthes Disease, in which the ball in the hip joint can grow mis-shapen. Such diseases – most visibly, polio – were treated by immobilising and straightening the limbs. McLaren, his legs in traction, was strapped to a bicycle-wheeled wicker gurney. Just 10 years later, as the youngest driver to have won a Formula One grand prix (the US GP in 1959), McLaren paid a return visit to the Wilson Home with his Cooper GP car.

The sleek white 650S likewise causes a stir when it pulls into the Wilson Home, to this day a rehabilitation centre for children. Director Russell Ness knows all about the car and its namesake. Russell races an historic 1967 Mini Cooper S, a faithful replica of a car that Bruce had raced during his Tasman Series visits.

“I learned after I came here that Bruce McLaren had been here,” Ness says. “That was fantastic to me. Bruce, Chris Amon, Denny Hulme… those guys were really big as I was growing up.

“I learned after I came here that Bruce McLaren had been here,” Ness says. “That was fantastic to me. Bruce, Chris Amon, Denny Hulme… those guys were really big as I was growing up.

“When Bruce was here, matron would come out in the morning and wonder why all the wheels were buckled on the gurneys. It was because Bruce and his mates would go racing on the grounds after lights-out. They’d be lying down with their heads propped up. They could wheel those things along pretty fast…”

Ness can draw a straight line between the 650S and that brilliant boy, who left here with his left leg some 35mm shorter than his right and went to study engineering. The attention of Jack Brabham and NZ’s inaugural Driver to Europe prize in 1958 took him to England and a drive with Cooper in 1959. He went on to establish Bruce McLaren Motor Racing and McLaren Cars in 1963.

“ He started something that I think has been amazing,” Ness says. “It’s a dynasty. Sure, the cars are quite different now, they’re being designed by different people and all that, but the name has survived – he started it. It’s been handed on, but that’s what happens. If you talk about the All Blacks, it’s not the same people – but it’s the same team, isn’t it?”

He started something that I think has been amazing,” Ness says. “It’s a dynasty. Sure, the cars are quite different now, they’re being designed by different people and all that, but the name has survived – he started it. It’s been handed on, but that’s what happens. If you talk about the All Blacks, it’s not the same people – but it’s the same team, isn’t it?”

We gun the syrupy, turbine-swift 650S away from the Wilson Home’s beautiful coastal setting. I begin to suspect that this car – and McLarens in general – is this good not just because of its attention to detail, but equally to practical smarts.

Take the gearbox. The seven-speed dual-clutch unit, which can operate automatically, manually, or both, is impressively smooth when dawdling in auto. But there’s something magic in its hardcore Sport-mode shifts, too. What McLaren calls ‘inertia push’ delivers a squeeze of throttle during upshifts, which helps iron out the rev drop when the higher cog is engaged.

I ponder how Bruce-esque that seems.

Twenty-four years ago I interviewed Denny Hulme, not long before he died of a heart attack while racing at Bathurst. After winning his world championship with Brabham in 1967, Hulme had joined his Kiwi mate for F1 and Can-Am.

Twenty-four years ago I interviewed Denny Hulme, not long before he died of a heart attack while racing at Bathurst. After winning his world championship with Brabham in 1967, Hulme had joined his Kiwi mate for F1 and Can-Am.

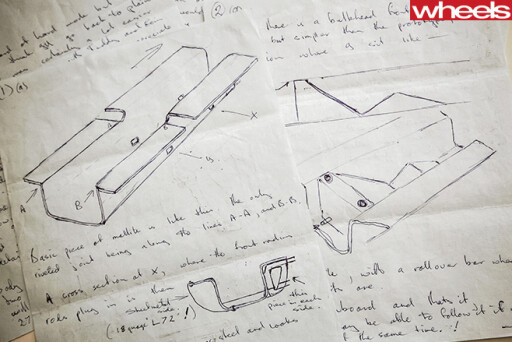

“Bruce was a very talented driver, but he was a good engineer as well,” Hulme told me. “Sitting on an aeroplane, he’d do a bit of a sketch and say to the boys when he got back to the workshop, ‘Make me that – I want to bolt that on tomorrow’. No matter how difficult it was, he’d just say, ‘Make it for me’.”

Bruce had been that way from an early age. When he was about 14, Pop McLaren arrived home one day with a race car, a 1929 Austin Ulster. Pop soon hated it, but Bruce pestered him to keep it. With help from the workshop, the lad was continually tweaking and testing, racing around the backyard of their new home, around the corner in Upland Road.

Bruce had been that way from an early age. When he was about 14, Pop McLaren arrived home one day with a race car, a 1929 Austin Ulster. Pop soon hated it, but Bruce pestered him to keep it. With help from the workshop, the lad was continually tweaking and testing, racing around the backyard of their new home, around the corner in Upland Road.

Devotion, exemplified

On the Tasman coast, about 40km west of Auckland, is Muriwai Beach. It’s almost obscured by fog and drizzle as we nose the 650S down the steep Waitea Rd. Far below us, beyond a spectacular drop, is a colony of gannets. Beyond the jutting headland, the pewter-coloured sands and wind-gnarled trees of Muriwai Beach stretch for miles. Pop McLaren often raced motorcycles there.

On this hill, then known as Quarry Road, Bruce McLaren made his motor sport debut in 1952. It must have been spooky for the 15-year-old, slithering a 750cc Austin up the steep, slippery, gravel surface – but he won the class. In second place was Phil Kerr, who would become a lifelong friend and joint managing director of Bruce McLaren Motor Racing.

On this hill, then known as Quarry Road, Bruce McLaren made his motor sport debut in 1952. It must have been spooky for the 15-year-old, slithering a 750cc Austin up the steep, slippery, gravel surface – but he won the class. In second place was Phil Kerr, who would become a lifelong friend and joint managing director of Bruce McLaren Motor Racing.

Kerr would also be there at the end, testing at Goodwood in 1970, when the rear bodywork of McLaren’s M8D Can-Am car detached at about 270km/h on the back straight. The car spun across the grass, slamming into a concrete marshalling post. Bruce was killed instantly.

So it was Kerr who phoned the boys at the factory to report what had happened. “Don’t bother coming in tomorrow,” he told them. But at 7:30am, every one of them was there. They just got on with it.

Here at Muriwai, with one of the world’s most admired supercars bearing his name, I wonder if that 15-year-old would ever have dreamed of this? I reckon he had.

Here at Muriwai, with one of the world’s most admired supercars bearing his name, I wonder if that 15-year-old would ever have dreamed of this? I reckon he had.

The fog lifts; I whirr back the electric roof and aim up the hill.

The 650S’s steering is quite possibly the most sublime I’ve ever experienced. It’s said to get even better at higher speeds, as the front aero tuning and the Brake Steer, which dabs the inside rear wheel, come into play. The two-pedal set-up is absolutely in key with the steering, the spacing perfect for left-foot braking.

In the whole, deceptively cruisy supercar package, the only real hint of racing-grade compromise is the metallic feel and squeal of the carbon-ceramic brakes.

McLaren’s 3.8-litre twin-turbo V8 has the sound of science. Some momentary ignition-cutting trickery in Sport mode produces an exhaust flare on upshifts, but in its sound and its utterly linear surge, it does lack the drama of Italian rivals.

After a reasonably brisk squirt from Muriwai, we arrive at yet another place of McLaren reverence.

The Waikumete Cemetery in Glen Eden is located on Great North Rd (oddly, the same road as the McLaren Auckland dealership). Bruce’s grave is on the southern side, on a gentle hill affording rolling views south toward Green Bay. Bruce lies next to his parents. Pop McLaren died in August 1985, 82 years old and just few months short of his ambition to see the McLaren team at the first Australian F1 Grand Prix in Adelaide. Ruth McLaren joined him at Waikumete in April 2004, aged 97.

The Waikumete Cemetery in Glen Eden is located on Great North Rd (oddly, the same road as the McLaren Auckland dealership). Bruce’s grave is on the southern side, on a gentle hill affording rolling views south toward Green Bay. Bruce lies next to his parents. Pop McLaren died in August 1985, 82 years old and just few months short of his ambition to see the McLaren team at the first Australian F1 Grand Prix in Adelaide. Ruth McLaren joined him at Waikumete in April 2004, aged 97.

Bruce’s widow, Patty, remarried in 1981 and lives in the UK. Their only child, daughter Amanda (now 49), only last year left New Zealand to take a role as brand ambassador at McLaren in Woking.

But it doesn’t end there. It won’t end at all. Jan McLaren won’t allow it.

A mark of respect

Bruce McLaren had two sisters – Pat, 10 years older, who died in 2007, and Jan, 10 years younger, but today with an energy and enthusiasm that scoffs at her 70 years. Since 1997 she has presided over the Bruce McLaren Trust, perpetuating the memory and the achievements of her big brother, a man who took on the world and won.

The Trust is headquartered in the old McLaren family flat in Remuera, above the forecourt where Bruce so often dismantled and redesigned his Austin Ulster. It’s where the pearl-white 650S, a heat haze rising from it, is now parked.

The Trust is headquartered in the old McLaren family flat in Remuera, above the forecourt where Bruce so often dismantled and redesigned his Austin Ulster. It’s where the pearl-white 650S, a heat haze rising from it, is now parked.

Each of the flat’s four or five rooms is piled high with display cabinets and shelves, packed with tinplate cars, astonishing trophies (like Monaco 1962, and the 1969 Can-Am ‘Floatile’ trophy), donated bits of McLaren racing cars, priceless driving suits.

Some of it is on loan from Patty McLaren-Brickett; a lot more besides has simply been donated by people inspired by Bruce and his achievements.

Some of it is on loan from Patty McLaren-Brickett; a lot more besides has simply been donated by people inspired by Bruce and his achievements.

“It really is like extended family,” Jan says. “And that feeling’s never, ever gone. A lot of the McLaren old boys say that even though they left McLaren, McLaren never left them.”

Jan and a volunteer assistant tirelessly document the race histories of her brother, fellow McLaren team drivers, and the cars prior to 1980, when McLaren was merged with Ron Dennis’s Project Four team.

Jan and a volunteer assistant tirelessly document the race histories of her brother, fellow McLaren team drivers, and the cars prior to 1980, when McLaren was merged with Ron Dennis’s Project Four team.

Thankfully, not much seems to have escaped the Trust. That first hillclimb at Muriwai? Jan has home movie footage of it. Between Bruce’s trips home from Europe, he made reel-to-reel tapes for the family, documenting race weekends and adventures. She has them all.

But the big question is what she thinks of the white car out front. “When I see a McLaren car like this one, it does give me great pride,” she says. “You know, there’s a man in England who’s got one of the [1994] McLaren F1 three-seaters – one of the XP cars, I think. When he got it, he had Ron Dennis put the Bruce McLaren Motor Racing shield on the back of it. Because, he said, ‘This is a McLaren. It’s not a Dennis’.”

But the big question is what she thinks of the white car out front. “When I see a McLaren car like this one, it does give me great pride,” she says. “You know, there’s a man in England who’s got one of the [1994] McLaren F1 three-seaters – one of the XP cars, I think. When he got it, he had Ron Dennis put the Bruce McLaren Motor Racing shield on the back of it. Because, he said, ‘This is a McLaren. It’s not a Dennis’.”

Fibre Diet

IN BRUCE McLaren’s day, the new miracle material for constructing chassis was Mallite, a composite sandwich of balsa wood and sheet aluminium-alloy.

McLaren’s first GP winner was more conventional, but chassis materials would be the re-making of the team. Its foray into carbonfibre came via former Brabham mechanic Ron Dennis, by then heading the Project Four team that dominated F2 and F3. With ambitions of F1, Dennis hired designer John Barnard, who was convinced carbonfibre was the material of the future. Marlboro, sponsor of both McLaren and Project Four, engineered a merger. The Dennis/Barnard vision of carbonfibre arrived in the MP4/1 of 1981 and F1 was revolutionised.

Skinned Deep

AS WITH all McLaren’s supercar family, the 650S is built around the carbonfibre MonoCell chassis, which weighs just 75kg. Such is its rigidity that the Spider requires no additional strengthening versus the coupe. To the MonoCell are attached extruded alloy subframes to carry the engine, transmission and double-wishbone suspensions. McLaren’s ProActive Chassis Control features active dampers that are hydraulically linked, which allows firm roll control in cornering, with no adverse effect on suspension compliance (hence ride comfort) when travelling in a straight line.

The 3.8-litre twin-turbo V8, which weighs just 199kg, is hotted-up from the superseded 12C’s with new pistons, cylinder heads, exhaust valves and revised cooling. Power and torque are increased over 12C by 37kW and 78Nm.

COMMENTS